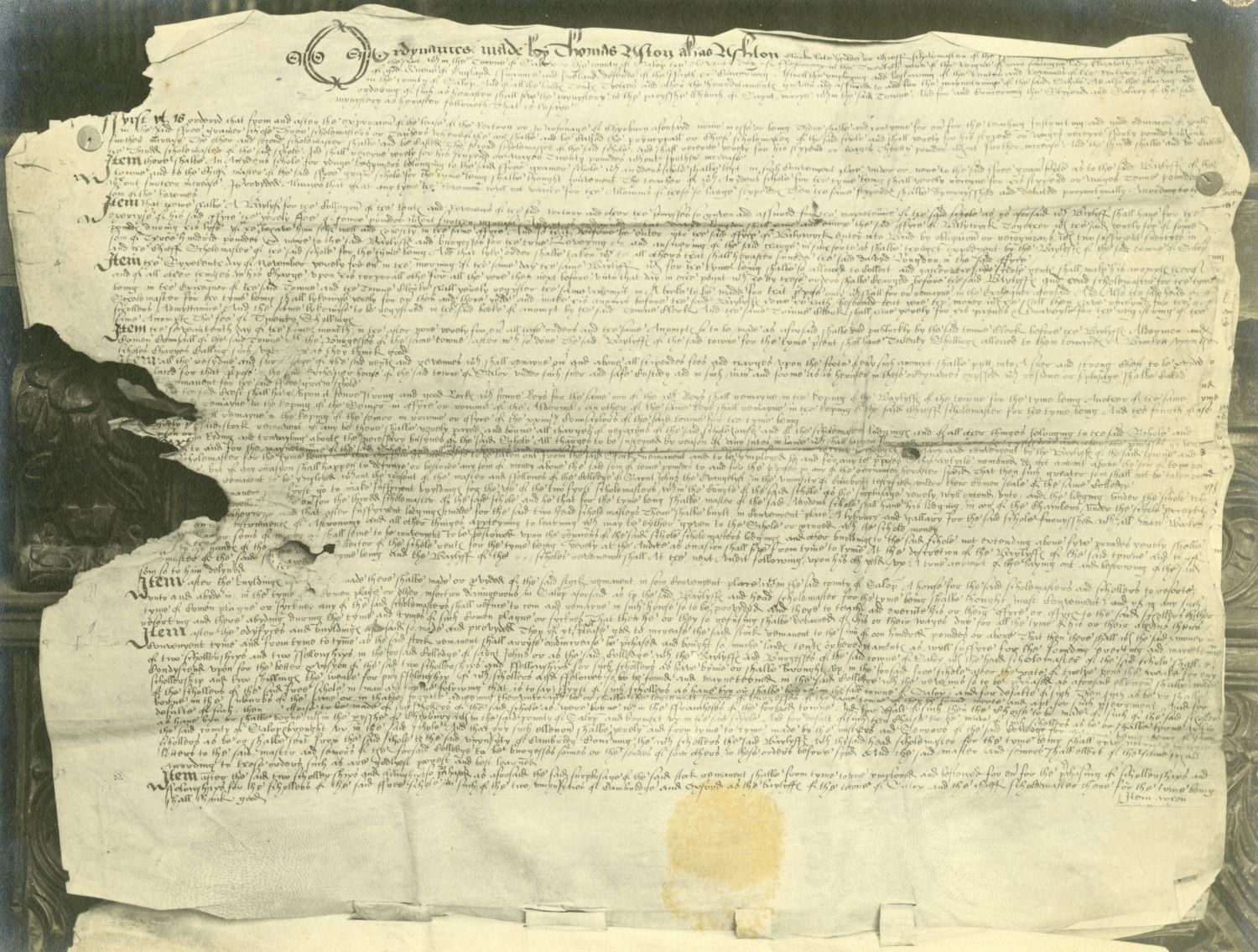

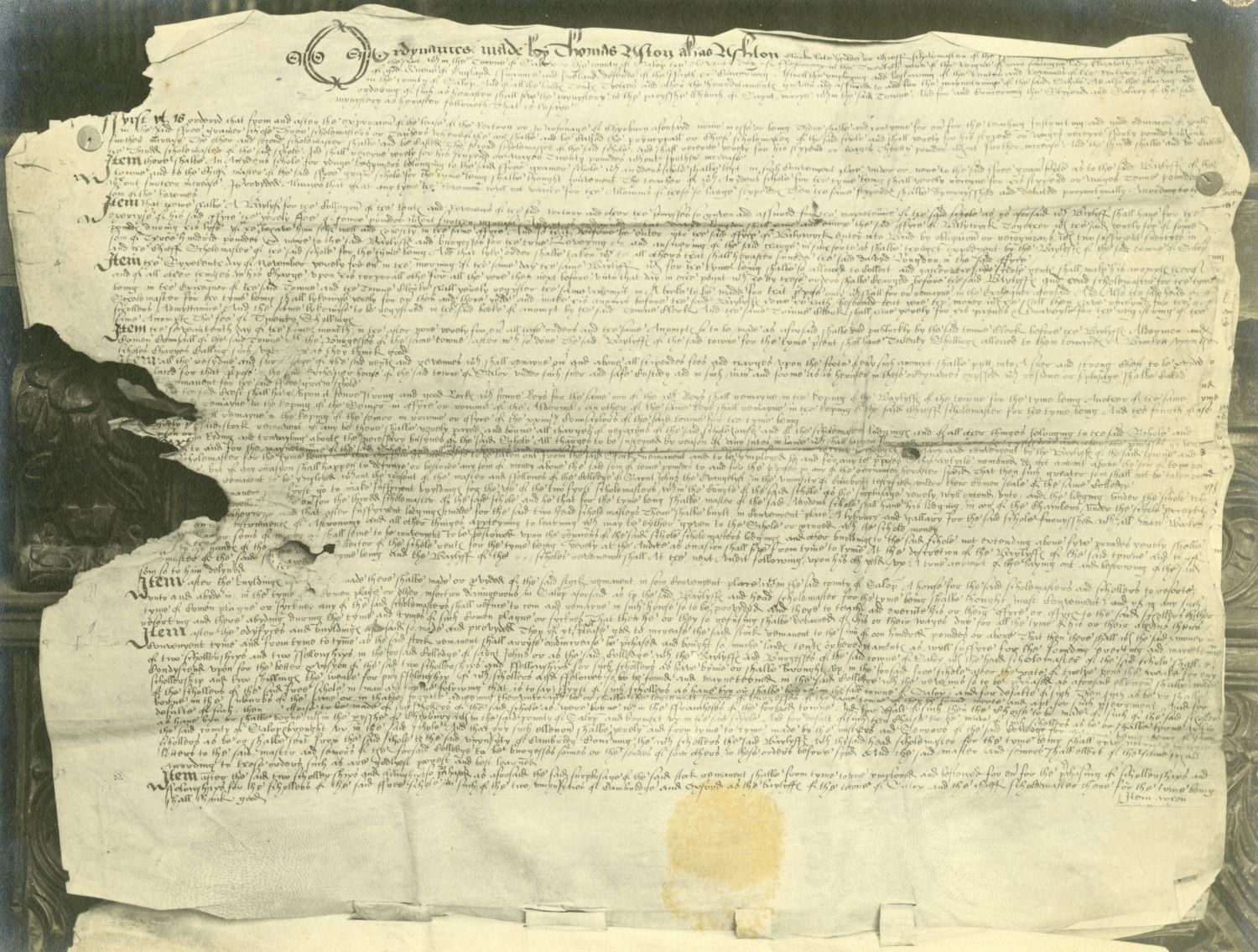

1578 - Ashton’s Ordinances

Ashton’s Ordinances for the government of Shrewsbury School were drawn up in 1578 and remained in force for over 200 years until 1798, when they were replaced by an Act of Parliament.

The original Royal Charter of 1552 had placed the appointment of the masters and almost the entire control of the School in the hands of the local Bailiffs of Shrewsbury, limited only by the advice of the Bishop of the diocese in making rules for its administration. During Thomas Ashton’s tenure as Headmaster, he succeeded in obtaining from Queen Elizabeth I an indenture, dated 22nd May 1571, granting him the right to draw up new rules for the general government of the School, as well as tithe revenues providing the School with additional revenue.

Photo: Ashton's Ordinances

Ashton retired as Headmaster a few months later, but he devoted a great deal of time, energy and skill over the next few years in negotiating and drawing up a new set of Ordinances for the School. In doing so, Ashton had to tread a delicate diplomatic line between ensuring that future Headmasters had sufficient independence to determine the direction of the School, while not alienating the sympathies of the town or causing resentment among local people of influence.

The final version of Ashton’s Ordinances was finally agreed on 11th February 1578, almost seven years after Ashton had retired as Headmaster. Under this new governing document, the appointment of masters was transferred to Ashton’s own college, St John’s Cambridge, who were to choose one man to fill any vacancy that occurred in the first three ‘Schools’. After the candidate had received the Bishop’s approval, the Bailiffs and Burgesses (and later the Mayors) were to nominate him to the office, unless they “shall mislike of such person upon any cause reasonable”, in which case they were to ask the College to make a new election.

In deference to local feeling, St John’s College was required to give preference to a candidate who had been educated at the School and, ideally, one who was the son of a burgess or, failing that, was born in the County of Salop. The consequence of these rules was that, until the repeal of the Ordinances in 1798, all the Headmasters and most of the under-masters were former Shrewsbury School pupils.

The Ordinances also set out the governing principles for the School’s financial affairs. The School accounts had to be read by the Town Clerk before the Bailiffs and Burgesses every November. As this must have been a rather tedious occasion, the Bailiffs were allowed to make up for it by spending up to 20 shillings on a banquet later in the afternoon.

The ‘stock remnant’, as the balance on the School account was called, was kept in a ‘sure and strong chest’ in the town Exchequer. It was to have four locks, the keys of which were to be held respectively by the Bailiffs, the Headmaster, the senior Alderman and the senior Councillor. The Bailiffs and Headmaster could draw from this fund for the maintenance of the school buildings and other necessary expenses, up to £10 a year. Any greater expenses required the formal consent of St John’s College. As soon as there were sufficient funds in the stock remnant, it was to be spent upon building houses for the Headmaster and Second Master, then for a library and gallery, and next for a school house in the country to which the School could withdraw “in the time of a common plague or other infection dangerous in the Salop”, and finally for scholarships and fellowships for Shrewsbury School pupils at St John’s College.

Ashton returned to Shrewsbury in August 1578 to set his seal upon the Ordinances and preached a farewell sermon in St Mary’s Church. He died a fortnight later, in Cambridge, on 29th August 1578.

Photo: School Seal