1939 – Cheltenham College, A School in Exile

In September 1939, shortly after the Second World War broke out, the Headmaster and Governors of Cheltenham College received a message from the Government’s Office of Works: the College buildings were needed for Government offices. Official regrets were expressed for any inconvenience, but a transfer of all pupils and staff would have to take place within a fortnight.

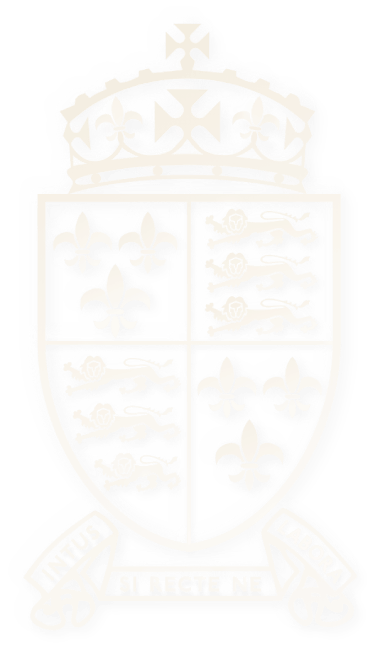

Photo: The two Headmasters: Mr John Bell (right), Headmaster of Cheltenham; Mr Hardy was Headmaster of Cheltenham before he came to Shrewsbury in 1932.

In the words of an outraged Times correspondent, signing himself ‘Harmodius’: “The Government flatly refused us any help in finding new accommodation. The Chapel, with its memorials to hundreds of old boys who died in former wars, is being used as a furniture store.”

Learning of their plight, Shrewsbury School at once offered Cheltenham refuge. With accommodation and facilities for 500 Salopians, surely space could be found to welcome an extra 400 Cheltonians…?

And with some hasty rearrangements, ingenious re-timetabling and inventive logistics, the two schools did indeed co-exist and function reasonably normally on the Kingsland site for two terms – until the Office of Works admitted that they did not after all require the College buildings, and Cheltenham were able to return home.

The story caught the imagination of the editors of the Picture Post, who despatched a journalist and photographer to Shrewsbury to write a feature article entitled ‘A School in Exile’.

Extracts and photographs from the article are included here.

“The improvised system was modelled on the life-patterns of Messrs Cox & Box. Nicely inter-locking timetables allow Shrewsbury to do lessons while Cheltenham play games, and vice versa. The system used up a great deal of oxygen in the classrooms during the black-out hours, but otherwise it has worked admirably. Occasionally, as Cheltenham come out of their first period of school work, they pass Shrewsbury going into theirs, on the staircase of the main school building. Otherwise, the two schools normally get few glimpses of each other.

Cheltenham have been scrupulously careful not to disturb Shrewsbury’s normal routine, except in the rare cases where it has been unavoidable. Superficially, the Salopians’ day is very much the same as it was in peacetime. For the Cheltonians, on the other hand, everything is new, everything is improvised. They live in billets about the town, in groups of half a dozen or less, instead of houses numbering fifty boys. They take their half-holiday on Wednesdays and Saturdays – but in the morning.

The Bursar has made his office among the oars and rowlocks of Shrewsbury’s boat house. The masters have made their common room in Shrewsbury’s cricket pavilion. Their musicians and bandsmen play bugles and cornets to the stuffed eagles in Shrewsbury’s Museum. Their professional cricket coach has constructed his sports-goods shop out of an old packing case in which a Curtis aeroplane crossed the Atlantic. Their place of assembly is Shrewsbury’s speech hall. During these months of living on top of one another, the two schools have shown an ingenious adaptability and a co-operative spirit such as gives the lie to the popular myth about public schools.”

In his book A History of Shrewsbury School, 1552 – 1952, Basil Oldham adds his own account of a unique sporting fixture between the two schools:

“In March 1940, during a period of very severe weather, the Cricket Field and Common were covered with snow, which thawed and then froze, with the result, completely unprecedented as far as is known, that the whole was a sheet of ice, and for several days both schools skated all over it. The ice was rough, but it was a thrillingly unusual experience, and at least one master skated the whole way from the Lane to the cinder path by Kingsland House.

The opportunity of finding a game which both schools played (or rather equally did not play) in which they could compete on equal terms, was too good to be lost; Shrewsbury and Cheltenham each hurriedly created a new office, that of Captain of Ice Hockey, and a match, in which the visitors were easily victorious, was played on the 1st XI wicket, and, like the Tucks Run, duly reported in the sporting columns of The Times, to the amazement of many Old Salopians who could not understand this sudden desecration of so sacred a spot.”

Photo: Ice hockey

Photo: Ice skating