1836 – Kennedy appointed as Headmaster

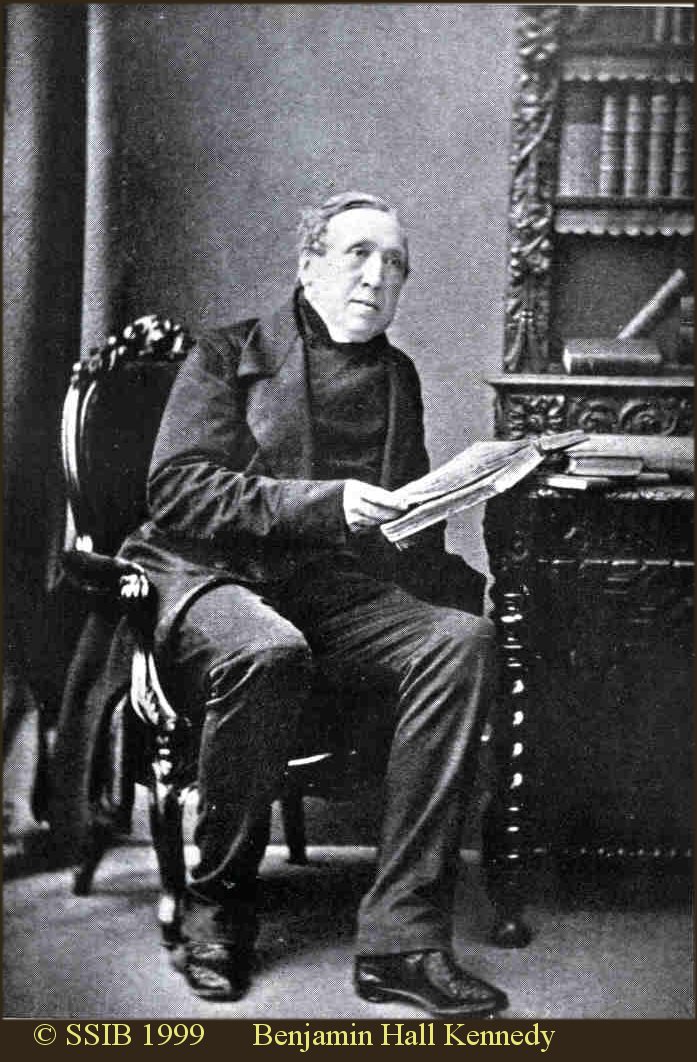

Benjamin Hall Kennedy joined Shrewsbury as a pupil in 1819 (the year after Charles Darwin) and shone academically throughout his years at the School.

While still a pupil at Shrewsbury, and without his Headmaster Samuel Butler even knowing it, he entered for two of the most prestigious Classics prizes at Cambridge and Oxford Universities – and won them both. He went up to St John’s College, Cambridge in 1823, where he continued his remarkable academic achievements.

When Butler retired in 1836 after 38 years as Headmaster of Shrewsbury, Kennedy succeeded him. He continued in post for 30 years and came to be regarded as the greatest classical schoolmaster of the century. His name is familiar to many who study Latin today, as the author of ‘Kennedy’s Latin Primer’. As David Gee notes in his book ‘City on a Hill’, “his status and reputation proved crucial when the Clarendon Commission was set up in 1862 to identify and inspect ‘Public Schools’”.

Photo: Kennedy’s Latin Primer

One of Kennedy’s first acts was to rent an additional playing field near the School. Although he was not a sportsman himself, he evidently attached importance to games – unlike his predecessor. During his tenure as Headmaster, the Royal Shrewsbury School Boat Club was formed, football (or douling, as it was called at Shrewsbury), the only compulsory sport, was officially codified at Cambridge University by a group that included three Old Salopians, and the Royal Shrewsbury School Hunt (cross-country running) – although strongly disapproved of initially by Kennedy, was eventually sanctioned.

The curriculum was widened, nominally at least, to include some teaching of modern languages, the extension of mathematics to four hours a week, and one week a term devoted to geography, when Butler’s ‘Historical Geography’ book was studied. From 1853, a half-hearted attempt was made to start natural science, but otherwise the focus of the curriculum remained the Classics. This was not surprising, given that he regarded the work of the School as preparation for a classical career at Cambridge or Oxford University.

He did experiment with a creating for a short time a ‘Non-collegiate Class’ for boys who were not destined for Oxbridge, which omitted Latin composition and all Greek, and included modern languages, English composition, history and extra mathematics. The Public Schools Commissioners showed considerable interest in this, but Kennedy was not enthusiastic.

Kennedy’s success as a teacher of the Classics is evidenced by prodigious achievements of his pupils at Cambridge and Oxford Universities. His teaching methods, however, were unusual. As Basil Oldham muses in his book ‘A History of Shrewsbury School 1552 – 1952, “The remarkable thing is that Kennedy achieved such success though he did nearly everything that the average teacher would avoid, and omitted most things that are generally regarded as essential.”

Perhaps Kennedy’s character as a teacher is best summed up in the words of his pupil and successor as Headmaster, Henry W. Moss: “His own undoubting faith in the worth of what he taught, the irresistible contagion of his enthusiasm, his kindling, inspiring, masterful personality – these were the secret of his strength… Nor could he conceal from us, however awe-inspiring at times were the ebullitions of his perfervid temper, how generous were the impulses, how kindly and affectionate was his disposition.”

Photo: Kennedy